June 6th, 2011

Significant Energy Use in Residential Cooling

Residential based electricity usage accounts for roughly 22% of the overall energy consumption within the US. Air conditioning alone uses over 20% of the total residential energy in the Western United States. Much of this energy use is due to the inefficiencies of your average home air conditioning unit. Though there are many alternative air conditioning options to reduce energy consumption for homes, they have yet to be adopted by residential building firms or the public at large.

One of the problems is the need for policy that would incentivize these more efficient systems. This will require a collaborative effort between the government, manufacturers and housing development builders. While this problem can be solved with some policy adjustments, the even greater issue for developers and the public is their confidence in these newer technologies. As it stands, a builder purchases tried-and-true standard forced air vapor compression A/C units because they are economical and reliable. A builder needs the assurance that these new systems will be just as reliable and require minimal maintenance before making a multi-million dollar decision to outfit a new community.

New Systems Require New Ways To Properly Test

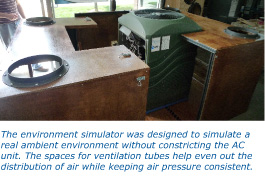

The Western Cooling Efficiency center at UC Davis is working on creating an environment simulator that will allow for the accelerated testing of these new units. Typically, air conditioner testing requires a hot environment. Unfortunately, this only allows data collection during a short period of the year during summer. Another problem with testing outdoors is that this testing is subject to the whims of weather, and may not be ideal for a true stress test. By controlling the air temperature that goes into the unit—the supply air—our engineers can stress test these new systems at peak temperature levels and determine their reliability at anytime during the year.

The system that is currently being tested uses a standard vapor compression system with an added twist: A small pump sprays water onto the condenser coil. This water helps absorb heat from the condenser coil which in turn reduces the amount of energy needed to cool down the refrigerant that will ultimately be used to cool your house. These systems can significantly reduce the overall amount of energy used to cool a space, but there is a bit of uncertainty regarding the effect and quality water may have on the lifespan of the condenser coil.

“Since we don’t know how long we would need to run a thorough test, we needed to create an environment that would allow us to run tests well past average usage times–the worst case scenario. This worst case scenario would run the unit for over 24 hours a day at a consistent air temperature of 95F,” says Curtis Harrington, an engineer on the project. This level of testing will determine not only how robust the system as a whole is, but it will accelerate the effects that water and water quality has on the system in a shorter time than if it was tested outdoors.

WCEC Researchers & Engineers

Theresa Pistochini

Curtis Harrington

Nelson Dichter

Written By

Paul FortunatoA Small Testing Environment Has Big Implications For Reliable Technology

The environment simulator works well at testing the effects of water on a system like the AquaChill, but its design is ultimately inflexible, “Ideally, we would have conditioned rooms to run accelerated tests on these types of systems because it would accommodate the varying sizes and form factors for these AC Units,” explains Curtis. Even though it cannot be refashioned to fit other units, the environment simulator is still an invaluable tool that will help push these new technologies towards a more reliable future, and will ultimately help increase their mainstream appeal.

In the world of energy efficiency, there is a fine balancing act between cost and performance. New technologies can help save you energy and money. Most of the time a higher up-front cost for an energy efficient A/C unit can be amortized over a couple of years from the energy savings. The main cost that challenges widespread adoption is the one that isn’t as easy to pinpoint. It is the unknown cost, whether real or internalized that these systems may not last as long or will need to be serviced more often than a traditional AC unit. This cost is what the WCEC intends to test for and ultimately help to abrogate, so industry and society can move to newer, more efficient systems without the looming specter of uncertainty.